Learning is a process that we can optimise

Why I believe there are countless opportunities to radically improve how people learn by addressing what makes it slow and hard.

I once heard that entrepreneurs' defining characteristic is their arrogance, or, more frequently, their naiveté, in believing that they can change the world.

It takes a significant amount of effort and risk to start a company. Developing a product or service from scratch and getting people to use it at scale is hard, especially so if it is a novel invention. If it were easy, someone would have done it already! Of course, some entrepreneurial types see an opportunity to make money and exploit it (the ads on my Instagram feed are a testament to this), but these aren’t company builders. In my personal experience, most of the entrepreneurs I know have seen a problem in the world and feel compelled to at least try to fix it. The source of their motivation comes from a deep conviction that a better way exists.

My deep conviction as an entrepreneur is that a better way of learning exists; I believe we can make learning quicker and easier for everyone. I think this now, and I felt it over ten years ago, long before generative AI fundamentally changed the toolset available to achieve this.

At times, this mission feels unrealistically ambitious, even to me. Learning is so fundamental to our experience as humans that such a broad goal is almost too big. From the moment we take our first earthly breath, our brain’s network of neural pathways changes continually based on new inputs. Our ability to do almost anything is predicated on our learning how to do it, whether consciously or not. The more we learn, the greater our capabilities and the greater our ability to help improve society in small and large ways. Knowledge leads to discoveries and innovations, which leads to progress.

Our ability to learn is the ultimate bottleneck for human potential.

Learning is also the most significant investment in our lives, in time and money. Global expenditure on Education and Training is predicted to reach $10T by 2030. There is no doubt about the impact access to education has on reducing poverty, which is one reason why nations worldwide are investing in achieving the UN’s SDG goal for quality education.

One would expect that with a matter this fundamental, with this many resources dedicated to its success, we should see significant and tangible advances as society and technology continue to develop. But when we look at our education system, workplace learning practices, and even our own personal approaches to learning, it is hard to argue that this is the case.

That is not to say that huge improvements have not been made. In the last 50 years, the rate of people on this planet with a basic education has gone from 60% to almost 90%. Assistive technology, such as text-to-speech tools that read content aloud, has brought access to better learning for millions of neurodiverse and visually impaired learners. Online learning offers flexibility for those with additional responsibilities or those who cannot commute to campus, opening access to millions more for whom education would not be possible. These are just a few examples; there are many more.

Things are improving, yes, but we cannot ignore the challenges. Up to 40% of U.S. undergraduates drop out of their programmes. The majority of college students today meet the criteria for at least one mental health problem, while staff and faculty are overwhelmed. Learners who were once considered ‘non-traditional’ are quickly becoming the new majority, but the design of higher education does not meet their needs.

The need for Better Learning is as great as ever.

Focus on the problem to find the solution.

For almost 15 years, I have been involved in building software products that help individuals facing various challenges learn more effectively. I have seen first-hand how a simple product can impact an individual’s overall learning ability and confidence. I have also seen how challenging it is to get simple but impactful products into the hands of individual students due to schools' purchasing priorities and budgets.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

This quote is often falsely attributed to Albert Einstein, but it is frequently repeated because it makes a good point: effective solutions come from first understanding the problem well.

I am not convinced that when it comes to better learning, we have a shared understanding of what the fundamental problems are yet. Or at least, I’m not seeing many people talk about them. There is a lot of chatter about skills and credentials, flexible pathways, different instruction models, digital transformation, big data, analytics, and gamification, but not much about how to optimise learning or the real learning challenges students face today. AI technology has immense power and potential, but until we are clear on the answers to these questions, how will we use it to enhance learning rather than replace it?

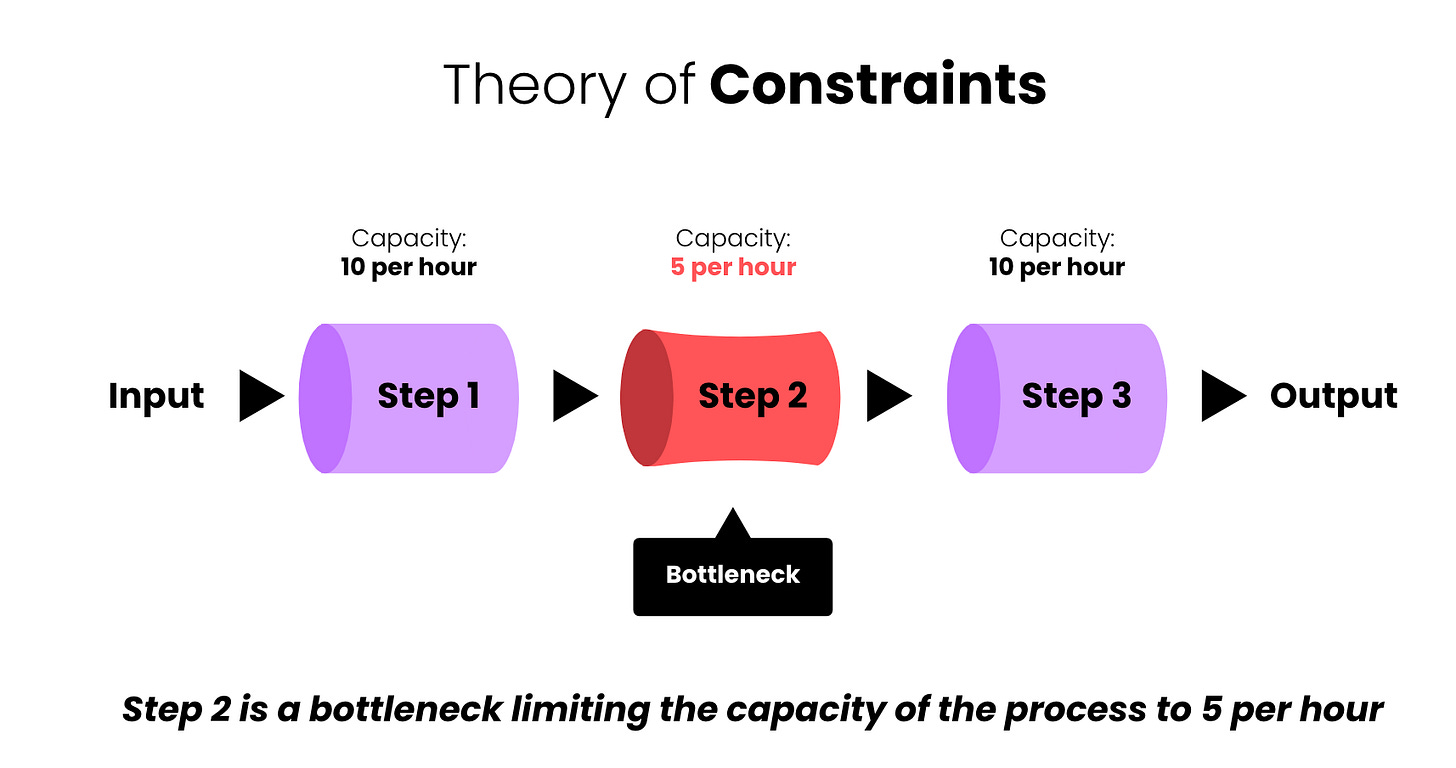

To improve learning, we should first understand what learning is and how it happens, i.e., the process of cognitive changes in our brain. From there, we can identify what is required for that process to be optimal and develop solutions to improve it for different learners and contexts. Like any process, there will be constraints limiting the rate of learning possible. Removing these constraints will make learning quicker and easier for that individual.

This might sound overly simplistic, but it is where we should start. Our understanding of learning sciences has increased significantly over the last 30 years. Some of that understanding has made its way into pedagogy and teaching practices, but defining best practices and changing human behaviour takes time. Sometimes generations.

Technology adoption happens at a much faster rate; ChatGPT famously gained 100 million users within two months of launch. Carefully designed learning tools and products, therefore, are a crucial component of improving learning and a means of driving change.

As a force multiplier, unconsidered use of technology can also lead to worse learning outcomes, as was experienced during the pandemic. This makes it all the more important that we use technology to improve learning rather than just change it or make it more ‘modern’.

The Theory of Constraints

There is no one single change that will improve learning for everyone. We all learn in different contexts, with different abilities and goals. A beginner and a professional golfer may play the same game with (essentially) the same tools, but the areas they need to work on to become better are very different.

To improve any process, you must consider the limiting constraint. That is, the thing you must change first to affect the overall outcome. A process is improved if the same output can be achieved with less time or with less effort.

Within manufacturing, where heavy investment is made in factories and labour to produce goods that need to be sold at a competitive price, being able to deliver double the items with the same resources is highly advantageous. There is a clear start and end point with stages in between, which makes it easier to identify where time is spent unnecessarily and to eliminate it.

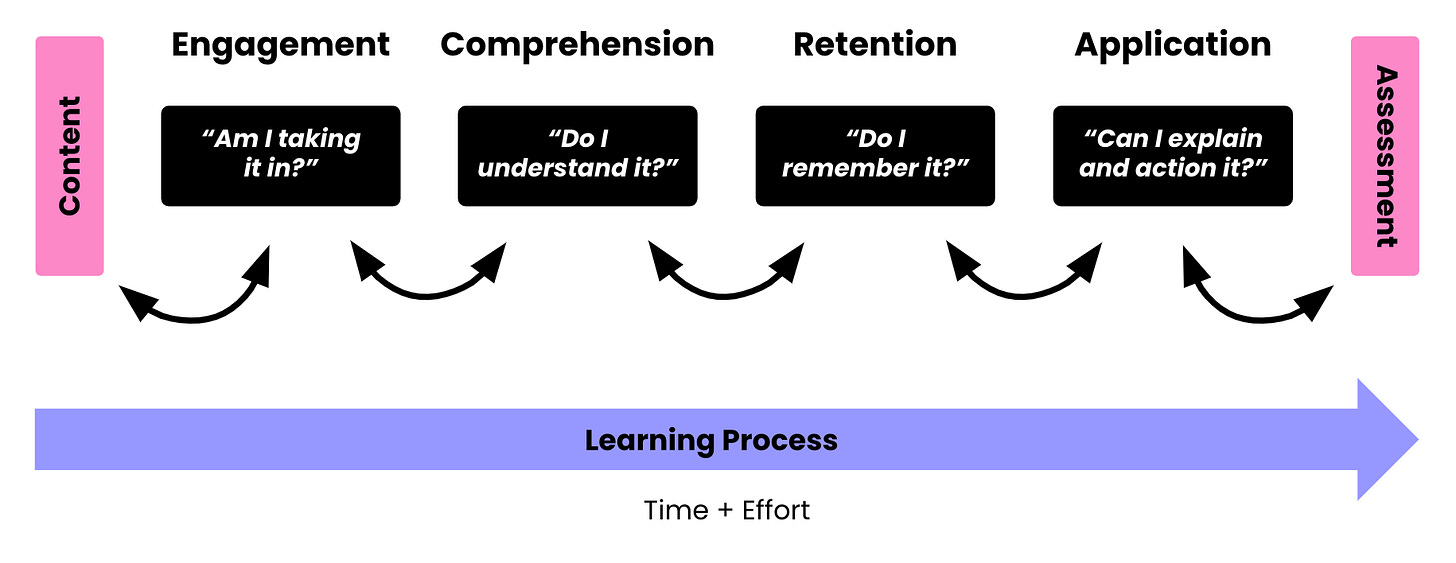

The learning process is less linear and far more complex. There are rarely clearly defined start or end points, and the way we approach education can further obfuscate the nature of the process. However, I think it is possible to plot a path from new information (the course materials) to successful application of that knowledge (some form of assessment). These stages, although abstract, help us understand what must happen for successful learning to take place.

By definition, to make learning quicker and easier, we need to reduce the time and effort spent to achieve the same level of learning. If I had 3 hours to study and spent 2 hours on my phone browsing socials or texting friends, it is evident that those 2 hours did not contribute to my learning. This is obvious, but there are countless, much more subtle ways that students spend time performing tasks which do not directly contribute to learning and can be eliminated. For example, you may spend extra time rereading passages, searching for misplaced notes or materials, or spending 20 minutes staring at a mathematics problem because you don’t understand how to solve it.

The Learning Effectiveness Spectrum

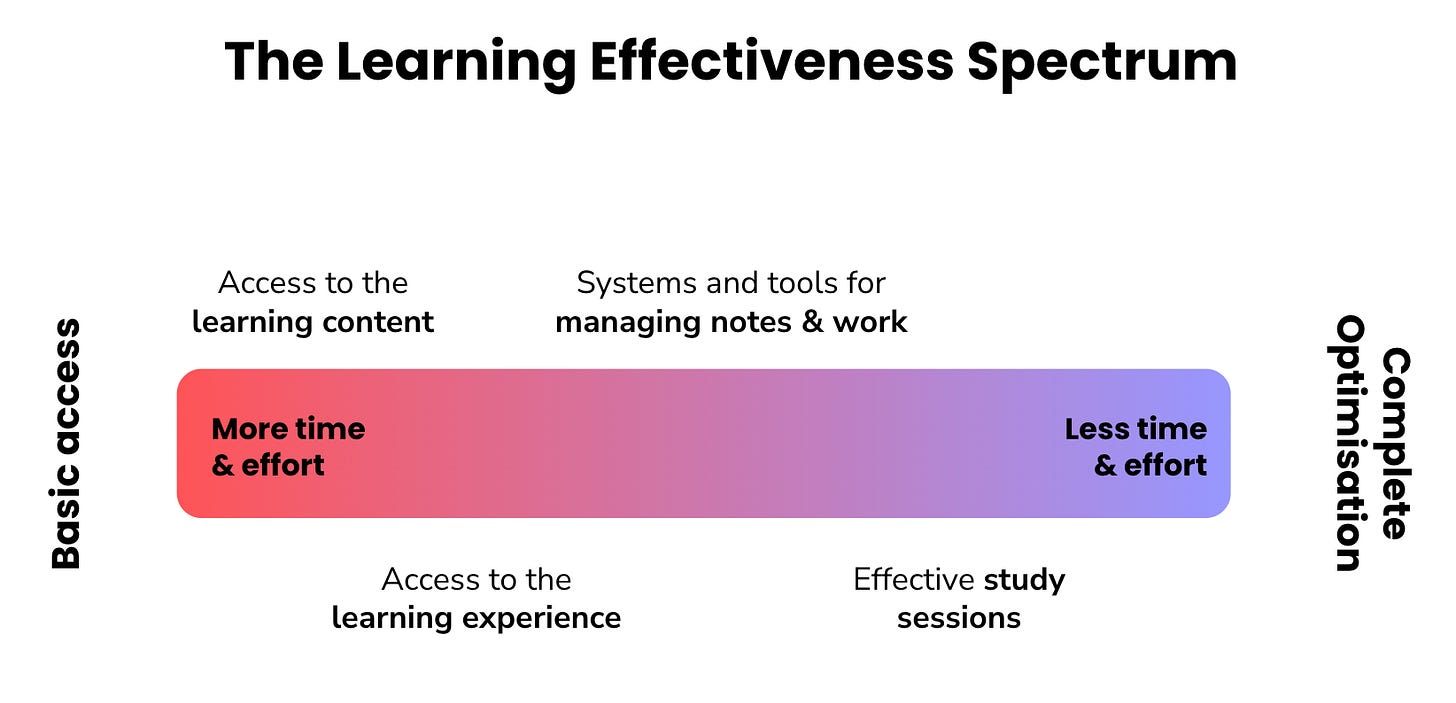

When thinking about how to improve something, it’s often useful to imagine two extremes to understand the polarities of a problem.

If we were to consider learning effectiveness on such a spectrum, we could define it as follows:

On one end is basic access—can the individual access the learning material, navigate the learning environment, and complete all the assessment tasks? If not, no learning can occur.

On the other end is complete optimisation - the individual using the minimum time possible to commit knowledge to long-term memory or develop a skill. Defining and measuring this is impossible, but as this is a thought exercise, that doesn’t matter.

The vast majority of learning happens between these two extremes. Challenges such as not being able to concentrate on absorbing the learning material or struggling to stay on top of deadlines fall towards the access end. Having an organized notes system that you use as the foundation for your assignments and test preparation or developing a daily habit of using a spaced-repetition system falls more towards the optimisation end.

I speak of this as a spectrum because a) it’s important that any conversation about better learning considers all people and not just those looking for productivity hacks, and b) all of us may face learning challenges along the spectrum throughout our lives.

In contrast to the golf analogy above, it isn’t that an individual sits somewhere on this spectrum and, over time, improves from one end to the other. Different learning environments and contexts create new learning constraints. Someone can find learning easier in one context and then struggle in another. For example, someone learning content in a second language may find oral instruction more cognitively challenging than written instruction (especially if the professor has an unfamiliar accent), while someone with dyslexia may find written instruction harder to understand. Depression, anxiety, and fatigue can all significantly impact someone’s ability to concentrate and process information, challenges which could affect anyone at any time.

Notice that accessibility is the start of the Learning Effectiveness Spectrum. Unfortunately, educational institutions often view accessibility as a compliance issue rather than a learning issue, and I think this is a mistake.

Accessibility issues need to be addressed first before any other learning can happen. Moreover, the most accessible designs are, more often than not, the best designs for everyone. A beautifully simple interface that is intuitive to use and minimises cognitive load may be necessary for some people to access learning. Still, it will also enhance the learning of those looking to optimise. By taking a more universal approach, we can have more confidence that our solutions will be suitable for more learners and learning contexts.

Learning in the Age of Information Overload

The good news is that the most significant access challenge has already been addressed.

Access to information is no longer the constraint to learning that it once was. Almost all documented human knowledge is now available online, accessible through our digital devices. There are hundreds of thousands (perhaps millions) of YouTube channels dedicated to educational content, repackaging knowledge in digestible ways. Every year, there are more ways to learn online, more products and services for accessing learning content and more content being produced. This will likely accelerate as AI makes producing educational content easier than ever.

We live in an exciting time where, in theory, anybody with access to a digital device can learn anything so long as they have sufficient motivation. On paper, this seems like it would bring about a sort of utopia-level of individual agency and opportunity to be able to do or be anything.

Of course, the reality is not like this. With new solutions come also new challenges. An abundance of information without the accompanying practices and tools to manage it can easily contribute to information overload, which in turn generates feelings of overwhelm, stress and a diminishing sense of confidence. Less confidence leads to less motivation, less motivation to less effort, and less effort to less progress, all of which create a constrained view of what one is capable of achieving. Too much information is like drinking from a firehose and can be a bad thing, especially as our capacity for processing new information is limited.

While the ways of ingesting information abound, the processes and tools for digesting that information are used far less frequently. Of course, this process of digesting information - segmenting larger pieces into smaller ones, interrogating each part to understand it and retaining what is valuable - is fundamental to the learning process and one that each individual must personally go through. But a process it is, and as such it is something that we can define and optimise.

We have a word for this set of strategies and techniques that enable individuals to learn effectively - study skills. Despite being, by definition, skills that improve learning ability, they are hardly mentioned in the context of how to improve student attainment or reduce dropout rates. Every educator knows they are important, but this importance is seldom reflected in priorities and budgets.

Access and optimisation are ends of a single spectrum. Developing solutions for one without considering the other creates further problems. As we increase access to more learning opportunities, we must also increase our usage of tools and techniques to manage the process of learning from that content. Our ability to harness the world’s knowledge is constrained by our ability to understand it.

Towards Better Learning

Why Better Learning and why now?

Put simply, there are considerable opportunities to help individuals learn better by using technology to address their personal constraints. For some, the most impact will come from having access to simpler and better tools for participating in the teaching and learning experience. For others, the impact will come from implementing more knowledge from learning science into techniques and tools for study optimisation.

For understandable reasons, most discussions about improving education are centred around changes to institutions, instruction, or the system itself. The new age of Artificial Intelligence has only recently begun. Although the implications of this technology over the coming decades are still unclear, we can be sure that it will accelerate our path to a more personalised education experience, one that is more centred around the learner.

We must remember that improvements to our institutions and pedagogy are a means towards the goal of learning, rather than the goal itself, and view our use of AI within that context. AI is a learning technology like we have not seen before and will undoubtedly lead to new standard practices for learning in ways we cannot currently imagine.

The scale at which learning happens means that even a slight improvement in how we learn will lead to a dramatic impact overall. There are currently 254 million students enrolled at university globally, a fraction of the number of people who would benefit from improved tools and techniques for learning, especially when considering future learners. In terms of a high-leverage activity to improve human civilisation, making learning quicker and easier for everyone must be one of the most impactful.

The fact that study skills and study tools are not a core part of every student’s toolkit only makes the potential for impact even more significant. I have experienced first-hand the impact of solutions addressing both ends of the spectrum, which is why I’m so bullish about the opportunities to make step-change improvements.

The world is going to change; that’s inevitable. I believe we can help change it in a way that makes learning quicker and easier for everyone. And if we work together, I don’t think it is naive to think we’ll succeed.